A group of homeless people gathers on the corner of Ninth Avenue and 21st Street in New York. Taxis brake and honk as four lanes of traffic roar downtown. A stifling breeze stirs the litter on the pavement.

Bishop Craig Anderson chairs a meeting at the General Theological Seminary in New York; he was inaugurated as its president on 21 September

Stepping through the plate-glass doors of an undistinguished Sixties Building unobtrusively labeled The General Theological Seminary is like stepping into another world. On the far side of the entrance hall a 19th-century-Gothic chapel links two tranquil quadrangles, their gardens plush with lawns and vivid with flowers despite New York’s heat.

The seminary. Established in 1817, was the first foundation in North America dedicated to the training of Anglican clergy. It is still the leading intellectual centre of the Episcopal Church in the USA, a position that imposes special burdens and responsibilities. And the man no bearing them, the new President of the seminary who was officially inaugurated last week, on 21 September, is Bishop Craig Anderson.

The Bishop, talking only in his study wearing the American academic’s traditional off-duty uniform of light-coloured chinos and crisp cotton shirt, with a touch of flamboyance in a loosely knotted tartan tie, is clearly proud of the seminary, and aware of the challenges it faces. “This is the General Seminary, so we need to contain all of the voices of the Episcopal Church, not be captive to one. A lot of people don’t want to hear that.”

And he knows his graduates will have to man the front line of the American Church – the parishes – into the 21st century. “Look out for the front door: we can’t train people for ordained ministry just like we used to. Seminaries ought to become dangerous places for teaching a subversive ethic. They should offer a more radical appropriation of the Gospel in our lives.”

Radicalism is the last thing Craig Anderson’s early career seemed to promise. After a stint as a U.S. army officer in the mid-1960s, the young Californian worked for six years as a marketing manager with the food company proctor and Gamble. It was a four-day recruiting trip for that company that changed his life: he went to Salt Lake City in Utah, the home base of the world’s Mormons, and left it deeply impressed by the religious commitment and sense of vocation among the young Mormons he met.

Uncertain of where his spiritual quest might take him, he left his home in Denver, Colorado, with his wife Lizbeth and their two-month-old son, to study theology, “not with a sense that I must become a priest: it was more an opportunity to seek, as one who has had a love-hate relationship with Christianity.

Doubt appeared as Anderson immersed himself in study. He was ordained in 1975, and in 1977 became Professor of Theology at the University of the South in Tennessee. There his two daughters were born, and the family settled down to college life in the sleepy town of Sewanee.

A promotion in 1984 turned their comfortable existence upside down: Craig Anderson was elected Bishop in the isolated rural diocese of South Dakota. This western state, perhaps best known in Britain as the magical prairie setting for the film Dances with Wolves, is the poorest diocese in the USA, and most of its churches are on Lakota Sioux reservations.

“That has been the single most definitive event. I was profoundly moved by how much of what I had to do with what I found there. From being a teacher, I discovered I had to learn: rather than being a proclaimer and evangelist, I had to be open to conversion.” For weeks at a time Bishop Anderson lived with the impoverished Lakota communities, in whose tradition people’s wealth and power are not judged by how much they own, but by how much they can give to others. He could not help contrasting this notion of giving as a way of life with the more measured pledge-giving of the parishes he had known elsewhere.

Gradually he began to see that for the Sioux the concept of holiness was tied no to the individual but to the community. The key was the idea of wakan, or the holy in all things. “They think of the Church as the holy family, an extended family related through baptism, where we have obligations to one another.”

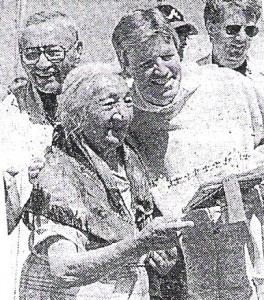

Learning from the Lakota: Bishop Anderson, wearing a buckskin chasuble given him by the Indians in South Dakota, with Zona Fills the Pipe

Sitting in his white-walled New York study, still without pictures on the wall and with only half his books unpacked, Bishop Anderson was clearly nostalgic for the West. Yet he stressed several times that he did not want to romanticize the Lakota. He is not what Americans call a “wanna-be” Indian, a disenchanted drop-out looking for escape. He sees his time there as “a gift, not to be applied uncritically, but as a corrective”, and his task now, he believes, is to brig that gift to the heart of the American Episcopal Church.

“I think we’ve become too issue-driven, too captive to the latest secular thinking. If we keep replacing tradition with the latest fad, people will begin to see the thinness of that. We’ve replaced”, he says, “our theological birthright with psychological porridge.” What he sees as having been left out is religious experience, transcendence. He wants the seminary to rehabilitate holiness, and breathe new life into Anglican spirituality. He sees action as springing form contemplation, and being the stronger for its influence.

Eight years of travelling and learning among the Lakota have revolutionized Bishop Anderson’s understanding of theology, which he calls “talking with God”/ For him it is no longer an academic study confined to libraries and examination halls: it has become a way of living that he wants every student at the seminary to experience and understand.

“Theology is a habit – a habit of the heart, the mind, the soul, born of and shared in common experience. Let’s talk about what it means to be in community; what our obligations to one another are, not just our rights. Recognising that theological education is a reformation experience, let’s try to reform ourselves in the image of Christ.”

He sees as part of this reformation consciousness the contribution of women clergy to the Church. He cheerfully admits that as Professor of Theology in the 1970s, he found the challenge from women students threatening. But no longer. “Now we’re finding women who are transforming the Church, calling for it to be more open, more caring.”

As he struggles to explain his vision for the Church, Bishop Anderson’s conversation is scattered with the names of theologians, anthropologists, philosophers and psychologists. But his aim is clearly not to intimidate; he seems to want to share the excitement of his own intellectual struggle, and to encourage others on the same journey.

In practice, this means going out and recruiting for the seminary, finding the bright young lights of the Church and fostering their vocation. It means opening the doors in the evening to those whom he calls seekers: students from any background who want to know more about God.

But he is no idealist, and he hasn’t a ready answer for every problem. He hesitates and looks out the window, as if for guidance, when discussing sexuality and how he should balance the individual rights of Christians and the teaching of the Church. He offers no solutions to the city’s casual violence, to the homelessness and alcoholism just outside the seminary’s doors. This saddens him; but far worse than “no answer”, he thinks, is “no hope”. Hope, for him, means dedication to the search, with a mind wide open to the unexpected.

“One of our greatest strengths as a Church is that we do embrace the world’s wisdom. I think that’s a great gift for those of s teaching people to talk about God: to be in conversation with the best of the Church and the best of the world.”

Church Times – October 1, 1993

Lesley Smith