One of the results of bishop Craig Anderson’s effort to reconcile South Dakota whites and Indians was a homemade bomb thrown at his house.

“Whenever you take a stand you’re going to excite the crazies,” said Anderson, the Episcopal bishop for South Dakota.

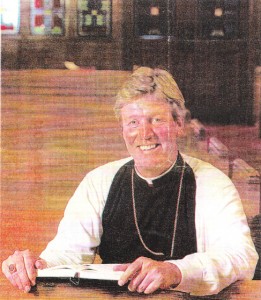

Craig Anderson, Episcopal bishop for South Dakota and member of the Council for Reconciliation, said he wants leaders to discuss substantive issues to aid the reconciliation effort

Anderson said two men drove by his house yelling obscenities, calling him an “Indian lover” and then threw the bomb, a Clorox bottle filled with hydrochloric acid and aluminum foil.

The bomb, which missed the house and fell into Anderson’s front yard, was thrown shortly after Anderson suggested that a presidential commission should be set up to discuss a Black Hills settlement.

“I think that’s part of what comes with reconciliation. It’s not all sweetness and light,” he said. “We introduced some substance and when it was introduced it tested the fiber of the community.”

The Sioux Falls Police Department has made no arrests and Detective Mark Jensen, who investigated the incident last month, said the people who threw the bomb may never be found.

None of Anderson’s family, which includes his wife, Liz, son, Court, and daughters, Megan and Ragnar, were injured.

Anderson said the incident points to the work South Dakota has to do to unite whites and Indians.

A native of Los Angeles, Anderson said he recognized that the state had problems with racism when he arrived here seven years ago to become the youngest bishop in the Episcopal church in America.

Part of the appeal of coming to South Dakota was a chance to learn about Indian culture, he said.

“I had an academic interest. When I came here to visit I fell in love with the land and the people. When people come here, I think they either fall in love with it or hate it.”

His journey to his job as South Dakota’s Episcopal bishop began with a marketing job for Proctor & Gamble in Denver.

Anderson’s job was to test market products including Biz, a pre-soak detergent introduced at a time when Americans weren’t pre-soaking their clothes.

Anderson had to convince consumers of the need to soak their clothes. His company worked with washing machine manufacturers to add a pre-soak to their machines.

“I was chasing the American dream,” he said. “I was single with lots of money and skiing every weekend. I was certainly not living a churchly life. I will leave that to your imagination.”

One day on a flight home to Denver, Anderson began to question what he was doing with his life. When he got home he talked to his priest and eventually entered the seminary.

After graduation he was a professor of theology at St. Luke’s Seminary in Sewanee, Tenn., before being nominated and named bishop.

In his current post, he heads the poorest Episcopal Diocese in the United States. It includes 111 churches, 75 which are Indian churches. More than half the members of the church are Indian.

Anderson said the makeup of his church gave him a unique perspective to serve on the Governor’s Council for the Year of Reconciliation and then the Council for Reconciliation.

The Episcopal church has dealt with many f the issues the state as a whole must deal with.

“I think it’s a wonderful mix and provides an opportunity to discuss differences,” he said. “We’re probably the only church that is half and half. We live with the differences.”

But one critic of the church and the bishop said Anderson doesn’t recognize and accept those differences.

Karen Artichoker, director of White Buffalo Calf Women’s Society in Mission, said her group’s womens shelter was evicted from a church building following a dispute about rent and control.

“It’s one thing to ask for help. It’s another thing to come in and take over. The church was saying, ‘You Indian women can’t do this we’ll come and do it for you.’ It’s racist,” she said. “We’re just really outraged that he sits on the commission.”

Artichoker said she tried to meet and talk with Anderson during one of his visits to the reservation but was told all discussions would have to go through the church’s lawyer.

Anderson said he tries to visit the reservation often. He has been trying to learn the Lakota language since he arrived in South Dakota and knows several prayers and hymns in the Indian language.

Francis Whitebird, the coordinator of the Governor’s Indian Affairs office, said one of his first impressions of Anderson came when Whitebird attended the funeral of former U.S. Rep. Ben Reifel, a service conducted by Anderson.

“They sang a beautiful hymn in Lakota. I thought this guy has his stuff together,” Whitebird said.

Anderson said reconciliation is a long process. Filling the Year of Reconciliation with programs to educate and inform South Dakotans about differences between the cultures was a good idea, he said.

He now wants to see discussion on substantive issues. That’s why he’s disappointed that the top elected leaders of the 11 Sioux tribes will no longer take part in reconciliation efforts.

Indian leaders said the reconciliation effort hasn’t dealt with important issues.

Anderson hopes they reconsider. “I don’t get all torn up, but I want to say, ‘Come back to the table. Part of reconciliation is to stay and not walk away.’”

-Corrine Olson – Argus Leader, Sioux Falls, S.D. – Sunday, June 30, 1991