Bishop Craig B. Anderson feels a calling to provide leadership to St. Paul’s School for the reformation of education in this country and the formation of character of its future leaders

It is easy to see why Bishop Craig B. Anderson has a deep appreciation of the gift of diversity, and why he believes celebrating this gift leads to a commitment to serve others.

From 1984 to 1993, Anderson served as bishop for the Diocese of South Dakota – a diocese of 118 congregations, 80 of which are on the “reservations of The Great Sioux Nation.” During this period he was head of the Governor’s Council for Reconciliation, and was twice the recipient of the Lakota Peace Medal, a recognition given to those who help combat institutional racism in the state of South Dakota.

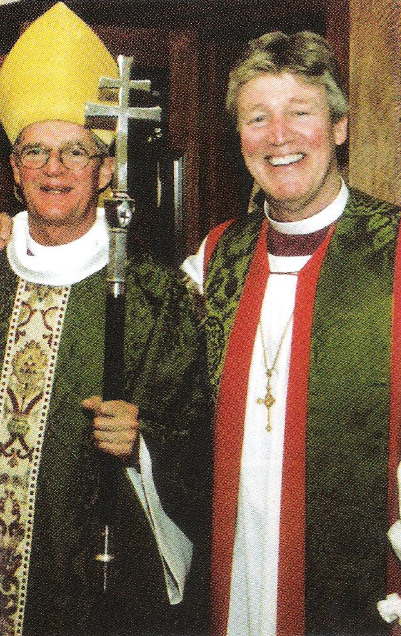

In June 2002, educators of 77 private schools from all over the world gathered at St. Paul’s School to explore the future of religious education. From left: Most Rev. Frank T. Griswold, presiding bishop of The Episcopal Church, USA and the Right Rev. Craig B. Anderson, rector of St. Paul’s School. Photo by Rez Gopez-Sindac

Anderson recently completed his six-year stint with the National Council of Churches USA (NCC) as president-elect (1995-1997), president (1997-1999), and past president (1995-2001). NCC is an ecumenical organization composed of 36 Protestant, Anglican and Orthodox communions (denominations), representing approximately 56 million church members in the United States. Anderson also represents the Episcopal Church to the World Council of Churches in the areas concerning racism and women’s participation in the church.

As head of St. Paul’s School, Anderson welcomes students from all kinds of racial and religious backgrounds, nay, even those who have no particular faith affiliation. Although primarily a Christian school, St. Paul’s School invites a diverse group of students and faculty members to create an extended family that respects and nurtures individual talent, personal freedom and responsibility, intellectual curiosity, and public service.

It is the school’s mission, says Anderson, to contribute to the formation of postmodern men and women with a global perspective.

Church Executive: How is St. Paul’s School preparing its students to be the future leaders of an ever-changing world?

Craig Anderson: St. Paul’s School prepares young men and women for leadership through service in their individual communities and the nation. It also participates in the reform of education in this country by developing a deeper curriculum which integrates the various disparate academic disciplines in preparing and providing a solid foundation for students to go on to college and graduate school. This challenge is also linked to a need for an even deeper curriculum in the formation of character, the teaching of virtue, and recognition that spirituality is an important part of the preparation of persons for servant leadership.

St. Paul’s School in many ways is a microcosm – we have students from 44 different states, 20 different countries and various religious groups. If we can develop a sense of respect and cooperation here at the school, we will be able to prepare a very gifted group of students that someday will become leaders in the fields of business, law, medicine, government and so forth, to not only tolerate other points of view but actually respect and embrace diversity in a deeper way. Our mission is to learn from one another, and in that learning we deepen our own faith. Our mission is not just to promote diversity because it is the politically correct thing to do, but to recognize that it is also the morally correct thing to do.

How would you explain your mission to embrace diversity in the light of the most recent controversy within the Episcopal Church?

There are churches that claim they know the mind of God, and there are those that say they seek the mind of God. I think the Episcopal Church is in the latter group. Unlike other Christian strains, Anglicans have never claimed to know the mind of God. Nor have Anglicans made claim to be infallible. Rather, Anglicans have sought the mind of God with humility, an openness to revelation, and a recognition of the need for ongoing reform within the church. Therefore we are not dogmatic. But the fact that we are a church that is open to diversity exposes us to opportunities as well as problems.

You mentioned that the Episcopal Church is a church that seeks the mind of God, rather than one that claims it already knows the mind of God. But isn’t the mind of God already expressed in the Bible?

The will of God is that all people should love one another. The will of God is that as Christians we love others through Jesus Christ. But we don’t know the mind of God on every question in the world. We are struggling with what it means to be fully human; we are struggling with what it means to be a sexual being; we are struggling with God’s gift of sexuality. We don’t claim to have all the answers, but we offer the certainty of a loving God made incarnate in his Son, Jesus Christ, and the ongoing presence of that love through the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Does that mean the Episcopal Church doesn’t know the mind of God on the issue of homosexuality?

Episcopalians generally have two clearly different points of view regarding sexuality in general and homosexuality in particular. It is important to note that there are some things that are important but adiaphora, meaning “things indifferent,” and some things that are of the esse – the Trinity, for example. There are some things that are not subject to debate, in a sense, given. But sexuality is something that has evolved. For example it wasn’t too many years ago that the Episcopal Church did not allow divorce and remarriage unless one had the permission of a bishop. Now divorce and remarriage in the church is common. It wasn’t too many years ago that women weren’t ordained; now we have ordained female priests. The fact of the matter is, some things change because the church is constantly caught up trying to find ways to provide theological answers to existentialist questions that come to us from the culture. There are certain churches, the Episcopal Church being one, that have, as part of their responsibility, taken on these difficult issues and tried to provide leadership not only for the Episcopal Church itself, but also for other Christians. I have a Roman Catholic friend who once said to me, “You Episcopalians take up the difficult issues, and you help pave the way for us to talk about them as well.”

While God may be ultimately unchangeable, God calls us to constant change, reform, repentance, and reconciliation, given our penchant for idolatry born of a yearning for security and solace in the face of chaos.

Look at the changes that we have seen. For example, we no longer think of women in the same way the Old Testament or even the New Testament writers did. And Jesus was instrumental in bringing about that change. Also, the position on slavery has changed.

I guess what I’m saying is the church’s teachings are always evolving. The tradition is never fixed and static. And because tradition is a representation of God’s interaction in human history with human beings, God is always calling us to something new. And its incumbent upon us to try to discern the mind of God without making imperialistic claims that we absolutely know what it is. These are the things that are of the essence, but there are a lot of things that change with time and tradition.

At a reception following the New York hockey games, Anderson finds time to celebrate with the students. The New York hockey games have been a St. Paul’s School tradition since 1896.

So where does the Episcopal Church stand right now?

I think the Episcopal Church and all other Christian bodies are struggling with the issue of sexuality in general and homosexuality in particular. The Episcopal Church in its resolutions has said that it recognizes gay and lesbian persons as children of God and full members of the church. However, we don’t advocate homosexuality as a lifestyle within the church right now. There are no liturgical rights to sanctify or bless these relationships.

I think the Episcopal Church is at an important crossroads. Some questions beg for answers. Will we recognize in humility the need for us to prevent the scandal of disunity? Can we work through our differences? I think the greatest scandal in Christianity is division, and I don’t think God has that in mind for us. Can we be charitable enough to go beyond moralism and recognize that all human beings are children of God?

How did the Episcopal Church address the administrative and business ramifications of the General Convention’s decision to consecrate an openly gay bishop?

There are several different layers. First, it has to do with governance and church polity. What does it mean to be a member of the Anglican Communion? Then within the Episcopal Church, what does it mean to be an Episcopalian recognizing that the primary identity of an Episcopalian is the diocese even though we live day in and out in parishes or congregations? What does it mean to be an Episcopalian given a diocese and autonomy on the one hand, and on the other hand the recognition that we are held together by a common liturgy and teachings? How much independence does the Episcopal Church in the United States, and the individual parish or diocese, have vis-à-vis the Anglican Communion worldwide? These are the questions that are being tested.

Second, it is a business issue. As you probably know there are a number of parishes and dioceses that are voting with their pocket books. Honestly, I have great difficulty with that. If the church is the family of God, when we disagree on something, we don’t withhold our commitment to our family, or we don’t use money as a way of getting our point of view across. I get very nervous when people and fellow bishops say they’re just going to take their money. And then there’s the whole question of property, building and pension fund.

But there are extreme efforts being made to keep the church together. I think the genius of Anglicanism is that although we disagree on many things, we have never split. For example, when women were ordained, a lot of people were talking about the church being divided. It never really happened. (There were a few small breakaway groups that comprise a very small percentage.) Right now we are at the same juncture again. But I think everyone wants to find a way of living together with a certain amount of disagreement. I think that’s possible, and that’s what we should strive for.

How long will it take before a resolution on the issue of money and property is achieved?

The presiding bishop and the archbishop need to attend to this carefully, deliberately and slowly. Also, whenever the church makes a change in doctrine or teaching, there is a period of receptivity where the change is tested against the leading of the Holy Spirit. Sometimes this period of reception can be rather lengthy.

As a former president of the National Council of Churches, you faced the challenge of a steadily declining attendance in mainline churches. Why do you think people are avoiding organized religion?

It is because we live in a narcissistic culture. Other cultures tend to define the individual person by virtue of their membership in a community. We, however, given our heritage, hold up the individual as the primary measure of what it is to be fully human, and a community is something that supports that. I think that has led us in some ways to an unhealthy narcissism, rather than a sense of community. When we have a culture of narcissism, religion becomes a personal thing. But religion, by its very nature, has to do with the weaving together and the formation of community. If you have this notion of religion as an individual pursuit, then it leads to an anti-institutionalism, and I think much of what we experience in the church today is an anti-institutional bias where people say, “I don’t need the church, I don’t want to be religious, I want to be spiritual.” I would suggest that that’s blatant nonsense. Spirituality is dependent upon being in a community of faith, and if it is not, it can be a very perverse, selfish kind of spirituality.

What has happened in the mainline churches to some extent is that they are seen as institutional and maintainers of status quo – and this may sound strange, but in some ways they are seen as antithetical to individual spirituality.

In the mainline churches there are a number of people who have left because the church didn’t satisfy all of their needs. What they failed to recognize is that they need to stop bringing about their needs and start giving back. But they say, “I will go where I will feel better and have easier answers.” If they don’t find what they want in a mainline church, they go someplace else. Unfortunately, sometimes mainline churches sell out trying to accommodate these people.

How are churches going to be effective and relevant in this generation?

They need to avoid a narrow denominationalism. They need to appreciate other traditions and recognize that we need to work together. I think seminaries need to develop leaders who will have a clear understanding of their faith, who will know their tradition, and who will be conversant with other traditions so that we can move beyond an ignorance born of a lack of in-depth knowledge of who we are as a church.

We need to avoid fads and quick fixes. We need to transcend our own individually held idolatries – issues that we think are of paramount importance. We need a strong leadership in the church – leadership that is birthed in prayer and walks in a deep kind of humility. To try to discern the mind of God in this present day won’t be easy because people want quick and easy answers. But I think the thing that will be worse at this point is apathy. I’m encouraged by the fact that we are arguing with one another with such conviction, which tells me that the Spirit is alive and working. I would be very concerned if people just didn’t care anymore.

What do you believe is the state of religion in America today?

I think religion is alive and somewhat well in the United States. I think the state of institutional religion is in need of ongoing reform. We are a most religious nation, and it is my hope that we can finally overcome a kind of unhealthy parochialism and begin to see that God intends for us to be one. If we can see through globalization that we are interdependent, that may help religion bring about the reforms that this country needs.

Church Executive, vol. 3, issue 4, pg 12