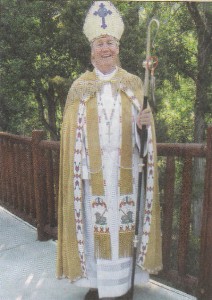

On Sunday the Rt. Rev. Craig Anderson will take his place behind the altar of St. Thomas Episcopal Church one last time in his role as interim pastor.

When he does, he’ll do so not in his traditional bishop’s dress but in a cope made of elk hide and a miter headdress covered with hundreds of tiny beads forming the Sacred Circle.

He’ll drape a stole around his neck, its beads depicting a lamb signifying his status as a shepherd of the flock and teepees with open flaps representing hospitality.

In his hand he will carry a silver crosier, or bishop’s staff adorned with a sacred circle made of porcupine quills and an eagle’s feather – permission to carry the feather granted by a federal judge.

The years that Anderson spent ministering to the Sioux in the Black Hills of South Dakota have left an imprint on this boyishly handsome man with sandy colored hair.

And he, in turn, has shared the wisdom he learned from them with his family at St Thomas over the past 13 months. He first greeted parishioners with an Indian greeting that means, “We are all brothers and sisters” and he has followed that up by teaching them the virtues he learned from the Indians.

“My experience there was the most profound part of my spiritual development. Always in the back of my mind—no matter where I am—I hear this voice: Don’t become enamored of wealth and all the rest. Remember the virtues. It shaped the rest of my ministry,” said Anderson, who spent ten years with the Sioux from 1984-1994.

Anderson was teaching at the University of La Salle when he was asked to consider being bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of South Dakota.

At first, he resisted—he was an academician, quite content to teach about other cultures that he had become so intrigued with.

But as he stood on the prairie of South Dakota, the grass up to his waist, he was moved to tears by the vastness of the land.

“There’s a scene in ‘Dances with Wolves’ where Kevin Costner is standing there with grass up to his waist. You can tell he’s fallen in love with the land. And I had the same experience,” said Anderson.

“They asked me why I wanted to be bishop, and I responded, ’Because I think you have something to teach us. We need, for instance, to learn a sense of land ethic. We need to learn a sense of community. We need to learn about how religion is not part of life but all of life.’ ”

From bishop to “Leading Eagle”

Anderson didn’t go in with rose-colored blinders. He was wary of the litany of despair he had heard so much about—the alcoholism, the poverty and all the other problems associated with reservation life.

“At first, all I could see were the problems. Then, I began to look past the problems to see the people and their virtues: perseverance, courage, generosity, and wisdom.”

One of the ideas Anderson came to cherish, for instance, was the emphasis on the sacred circle.

“The Lakota believe that each of us is a part of it but none of us is at the center,” Anderson related. “Contrast that with our own culture where the emphasis is on the individual and individual happiness—a focus that has spawned an unhealthy narcissism.

“All their meetings start and end with the greeting: ‘We’re all part of the sacred circle.’ It’s a symbol of wholeness and unity. And, even before they get to the agenda, they’ll go around the circle and give each person an opportunity to speak. Sometimes it changes the agenda entirely.”

One man, for instance, might say, “My grandfather just died. I’m in grieving,” Anderson said. And the others will ask, “How can we help you?”

They view the church as ‘this holy family’ And it truly is not just an institution. It is a family.”

Indeed, Anderson was adopted in the Ogala Tribe on the Pine Ridge Reservation. He was given the name Wanbli Tokaheya, or “Leading Eagle,” and a horse. And, according to the Indian lady who adopted him, he was given obligations, as well.

“Pray for us daily,” she told him sternly.

As an Indian, Anderson participated in a vision quest, he took part in sweat lodge rituals and he became privy to the Sioux ways of thinking.

Perhaps one of the best-known virtues is generosity.

“For them it’s not something one does in terms of charitable giving but it’s a mark of who you are,” Anderson said.

On generosity and courage

Generosity may have some of its origins in the fact that the early Indians traveled light following the buffalo. If you had it, you had to haul it so giving away possessions had a practical side to it, Anderson observed.

But the tradition has carried over to today.

“If I said I liked your sweater, it would be incumbent on you to give it to me,” he said. “We’re a culture of accumulation. We think things are going to make us happy. But we can’t receive God’s presence if we’re full of stuff. We need to realize that none of that is going to make us happy. We need to accept the biblical idea that we’re only fulfilled if we empty our selves.”

Anderson recalled one instance where he was trying to figure out how to get the Indians to tithe or contribute a tenth of their money to the church each Sunday.

“Tithing doesn’t make sense to us, even though it’s in the Bible,” one of the elders told him.

Anderson learned why a few days later as he attended the memorial service of a young man who had been killed in an automobile accident.

Everyone in the community was there, praying, singing and laying tobacco and food on the gravesite.

The family of the young man had prepared gifts of nearly all they had to give to each of the community members to remember the young man by. Then, at the conclusion the service, the community gathered around the family reconstituting their lives by giving them gifts to start life anew in the face of their loss.

“The elder asked, “What did you learn?” And I replied, ‘It’s not 10 percent—it’s everything, isn’t it?” Anderson recalled.

The virtue of courage was illustrated in the past by the practice of counting coup, Anderson said.

“It was not so much about killing but being able to sneak up on your enemy and touch them. They were saying: ‘I could have killed him but I chose not to,’ “ Anderson said.

Today the Sioux demonstrate their courage in practices like the Sun Dance. The young men run sharp pieces of bone through their skin. The bones are attached to long ropes fastened to the top of a sun pole and the young men dance around this sun pole pulling away from the pole until bone rips out of the skin –a process that may take hours.

It’s a sacrificial flesh offering given as part of a prayer on behalf of the community, Anderson said, and the young men bear the scars for the remainder of their lives.

On perseverance and wisdom

Anderson encountered the perseverance of the Indians when he worked with them on the Bradley Bill, designed to return the Black Hills to the Sioux. The government had promised the hills to the Sioux and then reneged when gold was found there.

But, as Anderson learned, the Indians believe that one’s identity is tied to the land and that’s one of the reasons they’re reluctant to leave even though conditions are so difficult.

They were calling us to our senses to respect the earth not in some sentimental way but because if we didn’t it would destroy us,’ said Anderson, who was honored with a Governor’s Award and the Sacred Hoop Peace Medal by the Great Sioux Nation for his work of reconciliation.

The Sioux also taught Anderson that knowledge always has to be tempered by wisdom—an idea he’s found useful in a culture that believes more information is better.

“The Lakota ask: How do you temper that information or knowledge to know how to do the right thing?”

They do it, in part, by couching everything in their tribal customs, Anderson said.

He recalled, for instance, watching a wizened old woman tell a group about her tribe’s history and customs.

One impatient young man kept asking her to tell about herself. After four interpretations, she looked at him and said, “You’ve not been listening.”

“Her identity was wrapped up in her tribe and its customs. That was who she was,” Anderson said.

Anderson and his wife, Lizbeth, who was given the name, “Buffalo Calf Woman Playing,” still go back to the reservation every year. They plan to return after their ministry at St. Thomas ends this week.

“We’ve lived so many places we’ve often felt as if we had no place to call home. That has become our spiritual home—it’s a very holy place for me,” said Anderson.

Anderson, who has served on the Council of Foreign Relations and as president of the National Council of Churches, said taking the approach he did with the Indians can be useful with all cultures:

“We think that we’re a superpower and that we’re going to convert everyone to our way of life. Some people go along with it for utilitarian purposes but they’re offended by it because it ignores their cultural values. It’s very important to look at religious and other values when we’re dealing in areas of foreign policy.”

By Karen Bossick

The Woodriver Journal

June 20, 2007