by Craig B. Anderson*

Anglican Theological Review/LXXVII:I

Called to guard and defend the faith and interpret and proclaim the Gospel. Bishops are ordained to be theologians given their vow to “share in the leadership of the Church throughout the world.” Good theology is dependent upon good theological method. The circular method described in this paper has been used by the House of Bishops for the past year and a half. The method is illustrated through examples from the life and work of the bishops.

A successful articulation of vision, however, depends upon the theologian’s ability to experience and to understand both the crisis of meaning of traditional Christianity in the “Post-Christian” period and the present crisis of traditional modernity in the contemporary “Post-Modern” world. If this dilemma is experienced, it cannot but become a theologian’s preoccupation, “haunting one’s dreams like a guilty romance.” – David Tracy, Blessed Rage for Order

I

So haunted, the Bishops of the Church, as theologians, are called by our contemporary experience of various crises to such a preoccupation, for such a preoccupation clarifies the vision and discloses the occupation of episcope as a vocation requiring dialogue. The need for such dialogue was recognized in a statement made by a bishop following the 1991 General Convention of the Episcopal Church in Arizona, “We cannot be Bishops alone if we are not first Bishops together.” A pithy theology undergirding the office, function and symbol of Episcopal ministry, the statement also sheds light on the nature of theology itself as a collaborative enterprise requiring dialogue. Such dialogue begins with prayer as an address to God with the expectation of a response. Such dialogue takes the form of active engagement with the texts of the tradition in the activity that we call hermeneutics, exegesis and interpretation. Such dialogue takes place and has taken place in the life of the Church in its councils as rhetoric, argumentation and deliberation in the face of the various crises (heresies) that face and have faced the Church throughout the ages. Such dialogue, and the need for such dialogue, is essential if the Church is to provide “a successful articulation of vision” given the “crisis of meaning of traditional Christianity in the “Post-Christian” period and the present crisis of traditional modernity in the contemporary “Post-Modern” world.”

Such dialogue is also experienced in the pastoral study, the confessional, the classroom of the Church and seminary, as well as the academy, the parish hall, or wherever and whenever two or three gather to speak as persons whose faith seeks understanding. Such dialogue is the meaning of theology in its original and most basic sense as a habitus, a habit and discipline born of sapientia (wisdom) grounded in the habitat of ecclesia; a habit of “the mind, the crown of the Spirit,” to echo Augustine. The habit of such dialogue as “God-talk,” like all language, follows a particular grammar, syntax, structure as well as employing image, logic, symbol and sign. And like all language, God-talk, while limited by its very structure in being able to fully articulate experiences of the ineffable, allows the theologian to transcend a captivity to immediate experience through the act of meaning-making by way of memory, reason and skill. Furthermore, such meaning-making is always qualified by the particular world, context or habitus of those engaging in such language. Stated simply, we engage the text within a given context or historical/cultural situation which shapes our appropriation and interpretation of how and what we express as “God-talk.” 1

As incurably religious beings, we give utterance to our experience of and about God through profession (in the original sense of “profession” as a religious response) as a theologate of all believers. Such profession through mediation in the context that we call koinonia is shaped by and gives rise to confessions(s) which in turn gives rise to doctrine and dogma as peculiar language pointing to the various modes or moments of truth disclosed or revealed in God-talk. 2 Such truth moves, or perhaps more accurately, drives, us to the acts or action that we call praxis or in-formed ministry; ministry informed by our experience of and reflection on our encounter with the divine within the human community that we call the Church, the people of God.

Such an understanding of theology helps us to retrieve not only the original meaning of theology as habitus but aids in a recognition that all human beings are theologians given our capacity to image and give expression to experiences of liminality. As such, a theological education is the birthright of every baptized Christian if we are to exercise in any meaningful way our Baptismal Covenant in the praxis that we call ministry. Such a recognition gives rise to a very practical question: “Who will guarantee the birthright, who will provide the theological education, and how will it be done?” While various answers come from within and outside the Church, I am increasingly convinced, based on recent experience, to include the General Conventions of 1991 in Phoenix and 1994 in Indianapolis that the bishops of the Church have a particular responsibility both collectively and individually as theologians who “articulate a vision,” as leaders ordained to exercise faithfulness “in prayer, and in the study of Holy Scripture… boldly proclaim(ing) and interpret(ing) the Gospel of Christ, enlightening the minds, and stirring up the conscience of (their) people and … guard(ing) the faith, unity and discipline of the Church, and shar(ing) with fellow bishops in the government of the whole Church.” 3

By virtue of office, symbol, and function, bishops are called to be teachers and exponents of the faith (“defenders,” if you will) and “doctors of the Church” 4 . Such a notion of a bishop as theologian helps to clarify the other elements of the ministry of oversight, particularly bishop as apostle, prophet, and as one who shares in the councils of the Church, and to take his or her place in a community of theological discourse. (theology as a habitus) leading to informed pastoral and/or prophetic ministry. 5 In this most basic sense of being a theologian, a bishop shares with all human beings the need to articulate the ineffable experience of God, but is called and ordained to aid others in that articulation in the mode of theological dialogue, not monologue. Thus ordained, how is such theological leadership to be accomplished? Such a question brings us to a consideration of how do we do theology, the question of theological method.

Why is theological method important? An important question especially given the charge by some that theologians today spend too much time on method and not enough time on truth claims, thereby revealing, a loss of theological nerve within the academy and the Church. While perhaps a legitimate criticism, I am using method in its most basic sense as a “normative pattern of recurrent and related operations yielding cumulative and progressive results.” 6 Such normative patterns and related operations when applied to theology require discipline in the employment of memory, reason, and skill given the fact that theology, in addition to being a collaborative enterprise, is also a derivative, secondary, or reflective enterprise. As such it is characterized by an investigation and consideration of faith’s realities and examines strongly held convictions and forcefully stated slogans by employing explicit criteria to judge the validity and truth of all claims inherent in slogan, ideology, commitment and theory. It is important to be clear as to the adequacy and appropriateness of such criteria, methods, and models in recognition that the method we use to frame our theological questions determines the answer. 7

If we view language as a system, code, game, or tool, it is essential to understand the system, decipher the code, know the rules of the game and have some proficiency with the tools. Theology as a derivative, cognitive and reflective activity employing language, word and reasoned discourse requires an understanding of the system (systematic theology), translation of the code (apologetics), knowing the rules/norms/ideals of the game (Christian ethics) and some proficiency with the tools (pastoral theology and/or praxis). Method in all branches, disciplines, sub-disciplines, areas and locations of theology is important, perhaps none more important than theology in its most basic form, theology as a habit of the heart, soul, and mind grounded in the criteria of wisdom that we call the embodied tradition within ecclesia. As such I am suggesting that bad habits and bad method beget bad theology. And perhaps even more basic, no method is bad method that results in bad theology. While an appropriate and adequate method in and of itself cannot produce good theology, a lack of intentional method or faulty method results in poor theology if we recognize theology as a habit or discipline of the heart and mind. To state the issue directly, theology is not ideology or slogan.

II

“Dysfunctional” was a word used by many to describe the House of Bishops, the Church, the clergy, the leadership, and the General Convention of 1991 in Phoenix. While I suspect that a variety of meaning and referents were intended by this term, which may or may not be accurate, it was a word that was used frequently to describe events leading up to and from the 1991 General Convention. While at times referring to unhappiness or dissatisfaction with decisions on particular resolutions/issues of the Convention, the term was most often used in describing the process and tenor of debate in both the House of Bishops and Deputies as confusing, lacking clear direction, destructive, tension-filled, chaotic, no sense of purpose, no way to resolve the issues, little clarity concerning the questions, concern over the lack of, use or misuse of scripture, tradition, reason, experience, and culture. In addition, some participants in both Houses reported feeling intimidated and cut-off by forceful speakers presenting strongly held views using inappropriate argumentative style and positions. In short, feelings of anger, fear, anxiety, frustration, confusion, and betrayal for many characterized both the process and resolution in addressing issues that came before the Convention. While it is beyond the scope or intent of this paper to provide a theological analysis of general Convention, it is my sense that one factor in the “dysfunction” and attendant feelings had to do with bad theology in large part born of bad theological method. Nowhere was this more evident than in those issues surrounding human sexuality and particularly questions relating to the blessing of same-sex unions and ordination of openly professing homosexual persons; a particular manifestation of Tracy’s “crisis” within “traditional Christianity” and the “Post-Christian” period and the present crisis of traditional modernity in the contemporary “Post-Modern” world.

Doing theology in our time is not an easy task. Within our “culture of disbelief” (as described by Stephen L. Carter) theology is suspect as an antiquated enterprise employing metaphysical speculation and remote from the concerns of the Church in the world. In this sense, it is viewed by many both outside and within the Church as a particular jargon spoken by a peculiar group of individuals called theologians who write and speak obtuse prose to and for one another in peculiar theological journals, published quarterly. Beneath this popular suspicion of theology is an intellectual suspicion of theology beginning with the Enlightenment. Once the Queen of the Sciences, theology’s demise in the academy/university can be seen as complete in the academic study of religion employing scientific methods to explore and explain religious behavior. Since Schleiermacher, theology itself has been, for the most part, confined to seminaries and taught as one discipline among many in preparing persons for the ordained ministry of the Church. 8 As such, theology is seen as something that in some way informs what “ministers do” and that few others understand or much less care about. But a more serious and sustained critique of theology can be found within theology itself. Have the authorities for theology been discredited in our modern or post-modern age? Do theological concepts and categories refer to anything real or are theologians “like stockbrokers who are trading shares on a nonexistent corporation? 9 Where does one find faith’s realities such as redemption, sanctification, salvation, atonement? Employing the warrants of scripture and the tradition in an attempt to produce faith’s realities through methods of citation and explication is, quite literally, epistemological nonsense. 10 Beyond this critique is the critique of patriarchal theology, leveled by feminist/womanist/liberation theology and “deconstruction” which views much of theology as an oppressive system which maintains an unjust status quo devoid of the praxis dimension of the Gospel which calls for action and participation, not removed reflection.

All of these new “masters of suspicion” undergird calls for more theological depth, leadership, and meaning in viewing the House of Bishops or the Church as dysfunctional. Calls for a “return to the Bible” or “traditional teaching” or “doctrine” all disclose a dis-ease, anxiety and lack of certainty given these various “suspicions” that are characteristic of our time and coupled with our culture’s loss of religious consensus, suspicion of authority, demand for instant gratification, impatience with ambiguity, privatization of religious experience, lack of institutional loyalty, and a certain cynicism regarding any and all institutions that results in a despair, a turn inward or a threat to leave if one’s demands (read passionate cause, position, rights, orthodoxy) aren’t satisfied. Given this crisis and that which undergirds it, it is hardly surprising that, as theologians, we are preoccupied; such preoccupation “haunting (our) dreams like a guilty romance.”

Doing theology in our time is not an easy task but a necessary one given our birthright and the fact that we are incurably religious, created to ask questions of and about God. It strikes me, however, that while theology is a difficult task, much of the crisis and dysfunction in the Church is in part a confusion and breakdown of “normative patterns and related operations” with regard to criteria, authority, and the adequacy of an explicit theological method.

III

So haunted, we left Phoenix. Preoccupied with the need to address our “dysfunction” and the crisis we sensed, the House of Bishops resolved to meet in a new way and explore our shared vocation as theologians. We resolved to move beyond captivity to a legislative method to employing a more explicit theological method. 11 We gathered at a new habitat (Kanuga Conference Center) and tried new habits (prayer, Bible study, small group discussions, a limited agenda and a consensual process) in hopes that a new habitus (koinonia/covenant community) might be realized. A new method was adopted. “A Hermeneutical Circle,” to guide our theological reflection; a method to which we now turn.

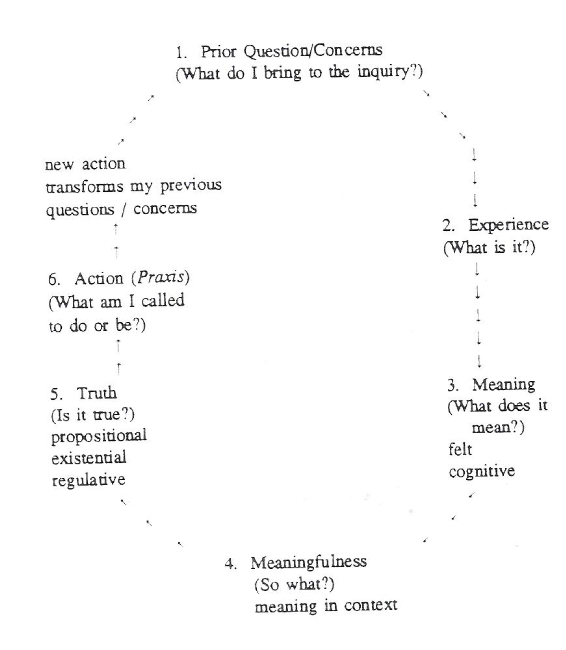

The method is circular and representative of doing theology from “below to above.” It presupposes the Anglican model of theological authority for meaning and ministry as discerned in Scripture, Tradition, and Reason beginning with the incarnational experience of God: 12

in briefly describing the method, I shall attempt to reflect on our experience as a House of Bishops to illustrate its use. As mentioned above, it has been my experience as a member of the House of Bishops that we have not been intentional or disciplined in using explicit theological methods, but have used legislative methods, i.e., Roberts Rules of Order, and a legislative process to do theology. Theology presupposes an appropriate and adequate theological method: legislation is neither an appropriate nor adequate method for doing theology. The legislative process has a legitimate place in the House of Bishops and councils of the Church, i.e. adopting a budget, but not for theological reflection. The legislative process inhibits the dialogue and collaboration necessary for consensus as a prelude to a sensus fidelium.

The method offered is not “the” but “a” method that has helped us to more adequately work together as theologians and as teachers of the Church. A brief comment on the method qua method should serve as a heuristic framework for both the elements and process of the method. First, as a circle, the method intends and attempts to acknowledge that theological reflection, although having directionality (Steps 1-6) has no fixed or required starting point. One can begin with any of the questions in any one of the steps. For example, one might ask of a statement, is it true (Step 5) and then explore questions of cultural context (Step 4) or meaning (Step 3) or, even more basically, the experience itself and the empirical evidence (Step 2) for the truth claim of the statement under investigation.

As a circle, the intent is to portray theological reflection as having direction, both linear and circular; linear in that theological reflection yields “cumulative and progressive results” and circular in that it is also “a normative pattern of recurrent and related operations.” 13 Said differently, theology begins with the multivalency of image and symbol as circular and related in an undifferentiated way in acknowledging the importance of intuition and imagination. However, theology differentiates experience through analysis and reason in an attempt to conceptualize and understand (verstehen). In recognizing that one can begin at any point on the circle, as Anglicans, given our incarnational proclivity, we tend to do theology from “below to above,” from experience to concept to truth to action. 14 Other traditions of theology, e.g. Lutheran “Confessional” theology, tend to begin with Truth (doctrine or dogma); the Augsburg Confession as a way to frame questions of not only praxis but also meaning and the experience of the believer or community itself. A further explanation of each of the six steps in the circle, illustrated by certain experiences of the House of Bishops since the 1991 General Convention, are offered to illustrate the method.

- Prior assumptions, questions, concerns (What do I bring To The Inquiry?)

Although a truism, we do not experience anything de novo, ex nihilo as a tabula rasa or in a vacuum. Our expense is already and always embedded and embodied in temporality, spaciality, language, intersubjectivity and especially in the case of theology but not restricted to theology, “lived theologies” replete with a system or “world” of values, attitudes, and beliefs. To illustrate: the Bishops of the Church brought their assumptions, attitudes, beliefs, convictions, commitments, feelings, thoughts, existential pressures, hopes and fears to the General Convention in 1991 as they do to any and all meetings of the House of Bishops. These “prior concerns” are the result of steps 2-6 (e.g., in relation to human sexuality, one’s experience of one’s own sexuality [Step 2]); the meaning and understanding one has of it (Step 3); the cultural values and social mores and lived theology of one’s diocese (Step 4); the teachings of the Church at various levels or within various contexts – canon, diocesan, individual (Step 5); and finally those actions that pre-condition our understanding of ourselves and any situation (Step 6). In short, the bishops bring their questions, prior concerns, convictions, ideological and theological commitments or “lived theology” to any and all meetings of the House of Bishops as a Council of the Church.

The first step in the theological method, regardless of whether or not it occurs first chronologically, is to find a way to share and express these concerns so that one can, as a theologian, be occupied by the text – human, written, or cultural – that is under investigation, and not be preoccupied by distractive concerns and commitments that keep one from paying attention fully to the experience under investigation. As such, the theologian is called upon to identify, make explicit and then “bracket” or put momentarily out-of-action such concerns and commitments so that he/she can attend fully to the issue/problem at hand. At Kanuga, the small group discussions provided a way to share these personal concerns and prior questions at the outset of each meeting. “Baggage” brought to the meeting, both personal and vocational, was shared in the intimacy of small groups. Similarly on volatile issues, such as human sexuality, there was an attempt to state “up front” strongly held beliefs, attitudes, and positions. While humanly impossible to literally “bracket” all prior questions, assumptions, and concerns, such sharing and dialogue have created a deepened trust essential for theology as a habitus.

Coupled with, and actually prior to, small group sharing of prior concerns, was the shared experience of prayer and Bible study. Lex orandi, lex credendi, first we pray and then we believe, to which I would add and then we act/minister. The act of corporate prayer in small groups aided us in bracketing our personal and corporate concerns. Small group Bible study helped us to see our concerns articulated in scripture. Several members of the House of Bishops have noted how timely and appropriate the Daily Office readings have been in our struggle with the issues before the House of Bishops. In short, worship and reflection on Scripture have provided the House of Bishops with a posture, disposition, and openness which aided in the sharing within small groups. Such prayer and engagement with the text provided a rather natural way for members of the House to state, bracket and move beyond a preoccupation and concern with self and hidden agenda toward concern for the Other in and with the other in prayer as a turning toward God and in rehearsing scripture as a way of understanding our shared script in community.

- Experience (What is it?)

Between 1991 and the General Convention of 1994, the House of Bishops at its interim and special meetings at Kanuga has focused and limited attention to fewer concerns and experiences with the intent of providing an opportunity and occasion for more sustained dialogue and theological reflection. Prior to such reflection, however, is the need to state, rehearse and understand the experience itself. A powerful example of this step in the hermeneutical circle came when several Bishops of color within the House shared their experiences of racism within the Church itself. The sharing took the form of open letters to members of the House of Bishops describing their experiences of racism.

“Thick description,” a term used by phenomenologists to move beyond “thin” or superficial description, is the goal of this moment in the hermeneutical circle. “Thick description” is the articulation of the complexity and multilayered nature of human experience versus simply assigned labels in the form of “isms” to people/groups and then treating the label or “ism.” “Thick description” requires attentive and active listening, paying attention to the person or group undergoing the particular experience to include the attendant feelings, thoughts and consequences.

- Meaning (What does it mean?)

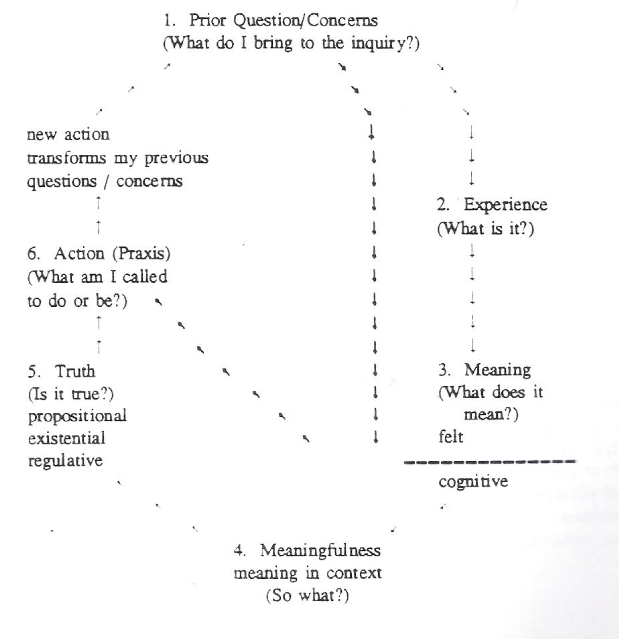

In sharing our experience and those concerns and commitments that inform such experience, we invariably ask the question unique to human beings; what does it mean? While questions of meaning are complex and multilayered, two types of meaning are of particular importance in theological reflection. The first, “felt meaning” refers to the values, attitudes, and convictions that each of us hold dear as individuals and as members of various organizations which are founded around a common cause or commitment, e.g., Episcopalians United or Integrity. “Felt meaning,” while incorporating personal feelings, goes beyond mere subjective preference to deeply held commitments and includes many of our deeply held conscious and unconscious attitudes, values and beliefs. Most of our actions and reactions are the result of “felt meaning.” While “felt meaning” is an element in theological reflection, such meaning is in need of the ongoing corrective of “cognitive meaning” or mediated response. In short, our strongly held convictions run the danger of becoming reactive ideology. Ideology, by its very nature, resists critique. Within theological reflection, felt meaning needs to be mediated, tested and subjected to sustained dialogue and argumentation employing warrants and evidence from the model that we as Anglicans espouse; scripture, tradition and reason. Within the House of Bishops in recent years, such mediation employing this Anglican model has been far too infrequent. The tendency has been to move from “felt meaning” to action, as illustrated:

The result of such a short cutting of the hermeneutical circle is reaction rather than thoughtful response born of responsible theological reflection leading to praxis. Why does this happen? Paul Ricoeur notes that “felt meaning” is the most basic and powerful motive for action but is for the most part reaction. The call for mediated response, cognitive meaning and the employment of reason through a retrieval and examination of scripture and the Church’s tradition within the existential context requires discipline. Such mediated response and responsibility is a critical element in theological reflection if we are to overcome a tendency in the House of Bishops and larger Church of holding strongly held opinions/ideologies, hurling slogans at one another, crafting resolutions, and using a legislative process which limits discussion and debate by prematurely “calling the question.”

Identifying our prior concerns, attending to our common experience and rigorously debating contemporary issues through reasoned discourse on scripture and tradition has the potential for not only a thoughtful response versus reaction, but through deep listening to the Other through the other, a chance for the movement of the Holy Spirit in mediated or revealed Truth leading to praxis. Hurling slogans, intimidation and a legislative process offer little room for the movement of the Spirit, in addition to revealing an inappropriate and inadequate method all of which result in bad theology.

Retrieving, examining and employing scripture, tradition and reason as the three-legged stool or model of Anglican theology requires some clarification. Scripture, tradition and reason are not weapons to be used to beat the other into subjection through modes of proof texting, explication, and application. Such a process is but another example of unmediated “felt meaning” wherein theology is reduced to ideology be it of the politically correct or incorrect variety. Rather the appropriate mode of using the Anglican model is “befriending” the scripture and the tradition through care and critical retrieval, investigation and appropriation. Such “befriending” reminds us that we always hear, read and interpret the biblical text and witness in the context of our prior concerns and experience. Said differently, we are called to move beyond a captivity to felt meaning, in functioning as a House of Bishops, to what Ricoeur calls a second naiveté born of differentiation and historical awareness.

The recent Pastoral Study on Human Sexuality by the House of Bishops serves as an example of the Bishops moving beyond “felt meaning” to a mediated and careful response in befriending scripture and tradition. Two facts illustrate this point. First, the creation of several “drafts” of the study and the ongoing dialogue and response that followed each separate draft of the document on human sexuality. Second, the change in the name of the document itself from a “teaching” to a “study” reflects the fact that the House of Bishops recognized that we had not arrived at a teaching/truth (Step 5) on human sexuality, and more debate, deliberation, and reflection is needed given the differing meanings and the meaning in context (Step 4).

4. Meaningfulness (Meaning in context, “So What?”)

In addition to befriending scripture and tradition in the exercise of theological inquiry and reflection, the theologian is called upon to befriend the context through an exegesis and interpretation of the culture, society, and historical situation in which the experience under consideration is mediated by “meaning.” Such meaning can be somewhat theoretical, abstract and obtuse if not grounded in the particular cultural, communal, historical, and personal context of the experience. “Meaningfulness” is the moment or step in theological reflection when both felt and cognitive meaning are relinked in asking the question, “So what?” or “How is this felt and cognitive meaning realized and embodied in the community or diocese of which I am a part?” To reiterate, the text is always read within a context. Our understanding of meaning is influenced by and subject to historical circumstances and the particular lived theologies of a local community. To illustrate: in developing the pastoral letter on racism, the Bishops in small group discussion related biblical and historical meanings of racism to their experience of racism in their respective dioceses. While the experience of racism was universally interpreted as sin (meaning), the particular manifestation of such sin varied given different contexts, e.g., environmental racism in larger cities, racism as a violation of property rights as well as human rights on various American Indian reservations, and particular forms of institutional racism in the deep South.

Meaningfulness as a moment in the hermeneutical circle brings us to the theological question of the relationship of Christ and culture. 15 In short, how does the meaning of scripture, the Church’s tradition and the exercise of memory, reason and skill aid in our judging and affirming the culture wherein we live and move and have our being as those who “profess” (in the original sense) Jesus as the Christ? To illustrate: the Pastoral Study on Human Sexuality adopted at the General Convention in Indianapolis is theologically a work-in-progress. It reflects Steps 1 through 3 in the hermeneutical circle. It became apparent in the course of discussion on the floor of the House of Bishops that the Bishops had not yet addressed the question of the various “meanings” of human sexuality cited in the document or considered these meanings in light of the Christ/culture or “meaningfulness” step. This important and essential step and work has yet to be addressed if the bishops are to avoid a reversion to old behavior which began to show itself in the two statements signed by various bishops in response to the final edition of the Pastoral Study. The test before the House of Bishops is whether or not we can resist the temptation to revert to old behavior. Furthermore, will we continue to remain in theological dialogue recognizing that significant work has yet to be done regarding this issue to include a theological consideration of the meaningfulness/Christ-culture question and the correlation of existential questions raised by the culture with the meaning and truth of the Christian witness?

5.Truth (Is it true?)

In building on Lindbeck’s understanding of truth in The Nature of Doctrine, three understandings of truth are important for theological reflection. The first and most obvious is “propositional” and tends to be characterized by linear thought and technical reason. It is the language of lawyers, logicians and the scientific community and also an important element in systematic theology. Since the Enlightenment there is a tendency to define truth as only propositional, verifiable, and scientifically demonstrable. Such a tendency is exacerbated by the triumph of technological reason in our culture and the demise of transcendental reason. Tracy’s fifth thesis in Blessed Rage for Order is instructive, “to determine the truth-status of the results of one’s investigation in the meaning of both common human experience and Christian texts, the theologian should employ an explicitly transcendental or metaphysical mode of reflection.” 16

Tracy’s thesis regarding an appropriate and adequate method point to truth as not only propositional but as existential/revelational and regulative. Various truths as revelatory of the Truth is “existential truth,” and understood theologically, is revelation, grace or gift. It is the “ah-ha” experience, being grasped by God’s Truth, that names and claims us. It is the awareness that God works through intuition and imagination in appresenting truth that is apprehended as transcendental Truth or revelation. It is this Truth that compels, calls and moves us. It is this Truth that drives us to prophetic utterance and justice. Such existential Truth is often experienced as God’s call to us. Such Truth, according to Rahner, Lonergan, and Tracy, results in the formulation of doctrine and dogma which inform the action of ministry as praxis. It is in this step, the completion of the circle, that we are reminded that all theology is ultimately practical theology. Truth as disclosive of and leading to praxis leads to a completion of the circle with the recognition that new insight, new understanding, and new action and behaviors transform prior concerns (Step 1) with the potential for converting and transforming individuals and communities. It is this existential understanding of truth, mediated by transcendental reason, that aids in our understanding of Jesus as the “Way, Life” and also embodied as the “Truth” of God.

In his treatment of Torah, Mark Dyer aided the House of Bishops in understanding truth as “regulative.” Torah as truth brings with it a regulative dimension for our life together as a Council of the Church and a covenant community. Truth as regulative allows us to see the need for Torah, not as a legal burden but as a gift that articulates covenant obligation and responsibility to the Other and other within ecclesia. It is a gift in that it transforms questions of human identity, as something to be achieved, to questions of human vocation in recognition that such identity is already given in covenant. Such vocation is found in the inseparability of the commandment to love God and neighbor. Such “regulative” truth gives shape, direction, and purpose to life within koinonia. To illustrate: the call for dialogue, collaboration, listening, discipline, and care that have characterized the House of Bishops meetings since our first meeting at Kanuga have been attempts to embody such regulative Truth.

6. Action (Praxis): What am I called to be or do?

Through a recognition of certain propositional truths (an analysis of our “dysfunction” as a House), existential truths (our “dysfunction” as a judgment and call for repentance, metanoia and new behavior), and regulative truths (in the face of such “dysfunction,” an agreed-upon metaphor and method to guide and structure our life together through common prayer, Bible study, small group reflection), the House of Bishops has attempted new action and praxis as a House of Theologians and Teachers of the Church. Increased frequency of meetings, a different format, new location, the employment of the hermeneutical circle as an intentional theological method, have resulted in a new mode-of-being-together as a House of Bishops. These changes have also resulted in an evolving “torah within the Torah” for members of the House of Bishops grounded in the images and metaphors of koinonia, covenant-community and an ecclesial community of theological discourse.

Coming full circle, methodologically speaking, has resulted in new action and praxis which has in fact changed our prior questions/concerns (Step 1). My sense is that there is a new resolve to continue our new pattern of meeting and adhering to disciplined theological reflection with methodological awareness and continuity. It is also my experience that when we are under internal and external pressure, the House of Bishops reverts to old behavior from time to time. There is however a difference in that we now recognize such reversion, usually name it and attempt to correct it intentionally. It is reasonable to assume that with continued practice our new action and behavior will become a new praxis embodying a new habitus. It is also reasonable to assume that such a new habitus and methodological awareness will result in the House of Bishops producing far better theology. These assumptions will be tested in the days and years ahead and if realized will require patience, care, sensitivity, and mutual respect for and with one another in our shared habitus, our shared “House.” This will further necessitate a willingness to share, to self-disclose, and to participate fully as members of this Household of faith. If such sharing is realized, the example of the Bishops as theologians of the Church has the potential for exciting and activating the theologian within every ecclesial community and baptized member. Such a sharing and willingness might help Bishops and all members of the Church to be free from the guilt that haunts our idolatrous preoccupation with self. Such a sharing and willingness might turn us in metanoia to God’s vision for us and call us all as theologians to articulate and profess such a vision with courage and resolve.

1 By text, I include not only the various written texts of the tradition, e.g. Scripture, but also what Anton Boisen has called the “human document” as well as the texts of a particular society and culture disclosed in its artifacts, social structures and institutions; those perduring features of a culture carried by image, symbol, sign and concept.

2 On different modes of truth, see George A. Lindbeck, The Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Past-Liberal Age (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1984) and his treatment of truth as expressive, intrasystematic, ontological, performative, and propositional (pp. 4 & ff). A dynamic treatment of truth can be seen in Edward Farley’s Ecclesial Reflection (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1982), especially Part Two and Farley’s treatment of theological portraiture, ecclesial duration and the ecclesial universal disclosing the different “forms” or ”moments” of theological truth.

3 Book of Common Prayer, Ordination of a Bishop, p. 518.

4 The historical and theological rationale for the conferral of the Doctoris honoris causa is an invitation to and conferral on the new Bishop to be a teacher and theologian. Without such an awareness, and referent, the degree is an empty honor, an undeserved title for a person without academic portfolio.

5 It is not accidental that the newly created College for Bishops at The General Theological Seminary begins with an exploration and reflection on the Bishop as Theologian and Teacher (Theme/Phase I) before addressing the role, function, office and symbol of the Bishop as Pastor (Theme II) and Prophet (Theme III).

6 Bernard Lonergan, Method in Theology. (New York: Herder and Herder, 1972). P.4.

7 See especially Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method (New York: Crossroad, 1985), Third Part, “Language as the medium of hermeneutical experience,” pp.345 ff.

8 For a unique and comprehensive account, a Sinngeschichte of sorts, of theology from its original form as a habitus and Science to its disintegration as a series of disciplines and sub-disciplines giving rise to the “theory-practice split” in theological education see Edward Farley, Theologia: The Fragmentation and Unity of Theological Education (Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1983) and its companion piece, The Fragility of Knowledge: Theological Education in the Church and the University (Philadelphia, Fortress Press 1988).

9 Edward Farley, Ecclesial Man: A Social Phenomenology of Faith and Reality (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1975), p. 6 ff.

10 Farley, Ecclesial Reflection, see Part One, “An Archeology and Critique of the House of Authority” for a compelling account of the collapse of the “authority” contained in scripture and tradition to include a critique of citation and explication as inappropriate theological methods.

11 Two papers presented to the House of Bishops at its first meeting at Kanuga following the 1991 General Convention provided a theological critique of the legislative method and offered new images and metaphors for the work and self-understanding of the House of Bishops. See Mark Dyer, “Torah: A Way of Life Called Episcopate” and Craig Anderson, “A Theological Metaphor and Method” and “Implications of Covenant Existence in Doing Theology as a House of Bishops” (March, 1993).

12 I first published this method as “A Theological Method,” in To Seek and to Serve, (Forward Movement, 1991), p. 364 ff.

13 Lonergan. Although not graphically explicit in either Lonergan or Tracy, such circular directionality is inherent in their treatment of transcendental (Thomistic) method. See especially Tracy, David, The Analogical Imagination: Christian Theology and the Culture of Pluralism (New York: Crossroads, 1981), Part II: “Interpreting the Christian Classic,” (p.231 ff.)

14 It is interesting to note the confusion, in this regard, as to the place of “experience” within Anglican models of theological authority. Experience is often accorded the status of authority alongside Scripture, Tradition and reason. I would argue that experience is the basis for these various authorities, i.e., in theology our reflection on our experience of God does not constitute a fourth source of authority per se, but is a priori upon which the script(ure), tradition and reason are dependent.

15 H. Richard Niebuhr’s classic, Christ and Culture (New York: Harper, 1951), pp.29 ff., and the five models for relating Christ to culture (culture defined as social fact, human achievement, a world of values, and pluralistic by its very nature) still serve as a good model for theological meaningfulness.

16 Tracy, Blessed Rage for Order, p. 52 ff.

*Craig B. Anderson Ph.D., the eighth bishop of the Diocese of South Dakota, is currently serving as President, Dean, and Professor of Theology at The General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church. He also serves on the Theology Committee, Communications Committee, and Planning Committee of the House of Bishops.

Anglican Theological Review/LXXVII:I