Alumni Horae – St. Paul’s School – Spring 1997

The following conversation took place on a Friday afternoon at the end of February while Rector-elect Bishop Craig B. Anderson, Alumni Association President William D. Vogel II ’80 and Alumni Horae editor Deborah de Peyster shared a conference call each in his and her respective offices.

Changing of the Guard – Bishop Anderson, left, will assume leadership of the School in July. L. to r. Alina Gillespie, Lizbeth Anderson, Interim Rector Cliff Gillespie.

Bishop Anderson has been elected eleventh Rector of St. Paul’s and will assume his post at the School in July.

Bill Vogel- The St. Paul’s community is extremely excited about your decision to accept the role of Rector for the School. On the reciprocal side, what aspects about being Rector of St. Paul’s School are particularly attractive to you?

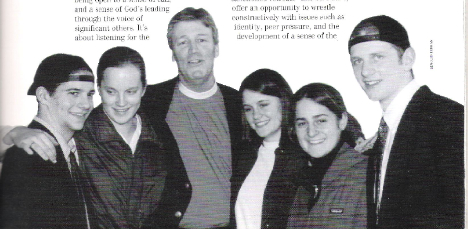

Bishop Anderson – In a word, the people. While I am deeply impressed by all the wonderful resources, the beauty of the grounds, and all of that which is St. Paul’s as an institution, what excited me most was meeting with the students, trustees, faculty, and staff. During the interview process I had an opportunity to visit with a group of students, representatives from the various Forms, and with some of the elected student body. The quality of the conversations, enthusiasm for the School, and their questions evoked in me an “Aha!” It was in the faces and voices of the students that I felt a strong call to come to St. Paul’s.

In addition, the voices and enthusiasm of the trustees, the seriousness with which they take their responsibility to hold St. Paul’s in trust, impressed me greatly. I’ve worked with lots of boards and have been involved in a variety of organizations but I have never met a more dedicated and committed group. It was clear that the School had a great impact on their lives. So that was another reason.

Bishop Anderson was drawn to St. Paul’s by its people and especially by its students. He is pictured below with (l. to r.): Luke Wolin ’99, Tracy Catlin ’99, Amanda Wynn ’98, and Alexandra Kumin ’98, and Gary Baronick ’99.

While visiting with faculty I sensed their struggle with curriculum revision that draws on the heritage and tradition of the past while being open to new pedagogy and educational philosophy. Seeing their commitment to a classical education and openness to new ideas was most impressive.

And then last, but by no means least, I appreciated and was grateful for the warmth and hospitality of the staff. In my mind, one of the best indicators of the health and welfare of an institution is how well the staff treats visitors. They clearly have a great sense of pride in being associated with the School. I saw no signs of animosity or contentiousness which are sometimes characteristic of an institution like this.

That’s a long answer to your question, but in a word, the people. The people at and associated with St. Paul’s.

Bill Vogel- Was the decision for you to come to St. Paul’s not really a career decision but formed more from your sense of calling and of vocation?

Bishop Anderson – Exactly.

Bill Vogel – I was wondering if you could elaborate a little bit on that.

Bishop Anderson – There are many ways of viewing ministry. One of the models that is sometimes used is the “professional model,” which has to do with ministry as “career.” I’ve never thought of ministry as a career. I’ve always thought of it as something that results from a call. Te word vocation from the Latin vocare or vocatio means call, responding to a call. If one looks at ministry as a career, most of what I have done would not make sense in terms of going from seminary to graduate school, to a teaching position, to being a bishop, to being a seminary president, to being a headmaster at a boarding school. Most people would look at such a “career” and scratch their heads.

Rather, “vocation” has to do with being open to a sense of call, and a sense of God’s leading through the voice of significant others. It’s about listening for the voice and leading of the spirit, trying to discern what that means, and then attempting to be faithful to what might be a call. I feel that in terms of St. Paul’s and I am very excited about it and the vocational possibilities and challenges.

Bishop Anderson and his wife, Lizbeth stand in front of the Chapel on one of their first visits to the School this winter

Alumnae Horae – When there is a sense of call there is also often a sense of being able to contribute in some special way. Do you feel you have something special to give to St. Paul’s?

Bishop Anderson – I hope and pray so. I have enjoyed teaching throughout my ministry and felt affirmed by it. It feels as though I am coming full circle in coming to St. Paul’s. Given my other experiences in ministry, as an academic, administrator, and bishop, I would like to think that I might be able to offer the benefit of such experiences to St. Paul’s in preparing persons for undergraduate and graduate education and even more importantly by sharing in the formation of values, faith, and what I would call character issues. It’s been my experience that locations for “sanctioned retreats” like St. Paul’s, offer an opportunity to wrestle constructively with issues such as identity, peer pressure, and the development of a sense of the common good. To have the privilege, and I do mean privilege, to come full circle and to return to education at the secondary level with new eyes and ears and to help shape a vision with others is important, meaningful, and exciting work.

Bill Vogel – That’s a wonderful segue into the next question. As you were alluding to character and the formation of character, I think about the whole topic of how far can we take a church school in the 90’s. How do you feel, as Rector of St. Paul’s, you would be able to build a community that certainly has at its center a faith in Christ but at the same time is not a turn off?

Bishop Anderson – Yes, that’s a very good question and central to the identity of St. Paul’s. But central to that identity is also the need to see the question in its context. We live in a post-Christian or post-Christendom age – an age that is increasingly secular and consumer oriented and some would say is without a clear sense of religious values. If that’s our context, it strikes me that if we are not only to maintain our heritage but have a living faith, we need to find ways and locations to not only know about it but live it. TO me, that’s what St. Paul’s embodies; a traditio, a living and evolving heritage which combines study, service, and sacrifice which is emblematic given the St. Paul’s coat-of-arms and its depiction of the Pelican, crossed swords, and book. TO live in an environment that promotes virtue and character – what better way to retain the heritage then by going to Chapel, by living in community, by struggling with the issues, by being open to what Scripture and tradition reveals, through living together in what I call a “covenant community.”

One of things that I find encouraging is that St. Paul’s School is open to a variety of religious expressions but has a clear identity. Essential to ecumenical dialogue, or faith sharing, or being open to other points of view is having a clear sense of your own. The best way to be religiously tolerant is to have a secure sense of one’s own tradition and be able to share it while respecting other traditions. If we can foster that we might be able to raise a generation capable of overcoming the type of violence seen in Beirut, Bosnia, and Belfast.

Bill Vogel – In a lighter vein, we wanted to ask about some of your experiences with the Lakota people. First of all, when was it that you decided that you were going to learn the Lakota tongue?

Bishop Anderson – When I was being considered for Bishop of South Dakota.

At the time, I was in Sewanee teaching. We had just built a house and I was ready to settle in to write books, teach, and live the quiet life of a seminary professor. I was in my office one day when a student came to me and said, “We tried to elect a Bishop of South Dakota, and after thirty-three ballots somebody stood up and said, ‘Let’s go home, the spirit isn’t moving, it’s starting to snow, we’re going to get stuck if we don’t get out of here.”

It was in 1983 when he was sharing this with me, and he said, “So, I am here to talk with you about being Bishop of South Dakota.” I said, “What?”

South Dakota is the poorest diocese of the church, and tough duty. It’s a very demanding place. He went on to say, “In class you’re always talking about tribal versus individual identity… Why don’t you put your ministry where your lecture is?”

There were twelve finalists in the election. I was the youngest and the only candidate who had absolutely no experience of South Dakota. So when I went to one of the reservations and one of the Indian priests said, “What do you know about us?” I responded, “Very little but I would come without prejudice and I would come wanting to learn.” And he said, “How much?” And I said, “I think that language carries a culture, so I am very interested in learning the culture and learning the language.”

It was clear to me that the Indian people elected me since they comprise the majority of members in the diocese. Unlike many who want to “save the Indians” I said I didn’t come to save them. I figured they had already been saved. They had a Savior. I said I would come and try to be a friend and a pastor and look past the despair and poverty of the reservation to the deep sense of holiness that I saw in the people and the land.

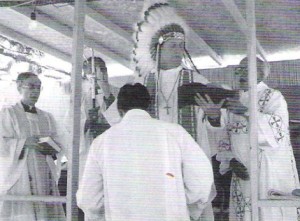

When I arrived in 1984 with a very young family they had an adoption ceremony in the St. Julia’s Church in Porcupine, South Dakota. That’s when I was adopted by the Ogalala Tribe and given the name “Wanbli Tokaheya” a name that means “Leading Eagle.” The name was given as a vocation, a call. It was a call to be a spiritual person, as bishop, to be a spiritual leader. It was an invitation, a mandate, a hope. I was very moved by the adoption ceremony. It has been and continues to be a strong image for me in my ministry.

On the Reservation – In headdress, Bishop Anderson ordains Webster Two Hawk on the Rosebud Reservation, June, 1987.

The adoption ceremony took place at an Evening Prayer service. Thousands of people were gathered in a huge circle when we were brought into the center of the circle. I had very young children at the time and their eyes were as big as saucers. We sat on a star quilt and were prayed over and offered sacred food. Sweet grass was used as incense. We didn’t understand any of the language at the time. They sang honoring songs for us and finally a little woman came up to us and told me to stand up. She spoke sternly to me in Lakota, which I didn’t understand, and said that I was her adopted son. She went on to say that I now had an adopted family and I had certain obligations. I had to pray for my adopted family daily and visit them regularly.

Following the adoption rite, we were taken back to the circle and taught how to dance as part of the circle. The dance was the final act of incorporation.

Bill Vogel – Is it true that you have a headdress?

Bishop Anderson – Yes, I sometimes wear it on St. Francis Day when I bless the pets. I was also given a cope, chasuble, and stole made from buffalo hide and decorated with intricate Indian beadwork. I think we could have a wonderful ceremony on St. Francis Day or Native American Day at St. Paul’s. The headdress was very special and given to me along with an Eagle feather when I was adopted. I carry the feather on my crosier. It’s a reminder of my family in South Dakota.

The experience and ministry in South Dakota was one of the most spiritually important parts of my life. It hearkens back to what we were talking about earlier about being open to other cultures and other religions. The nine years in South Dakota gave me a clear sense of my own Christian identity, through living with a people who see God in all of life. They don’t confine religion to one hour on Sunday morning but find God in every aspect of life and in all of Creation.